It looks like a Photo, it must be Art

How often have we heard someone dismiss a piece of art because it doesn’t look like a photograph? Conversely, because an art work looks like a photograph doesn’t make it art. It is almost as if a work of art has to conform to a given set of visual rules, before some people will accept it as art. This means of judging art stems from the premise that there is a link between how something is perceived and the skill with which that perception is portrayed.

These two concepts: perception and technical skill become the basis on which so many judge art. This is a shame, because it is such a limited and misguided view. In this blog I’m just going to consider these two ideas and show just because it looks like a photograph it is necessarily art.

Perception

Perception is a process by which the retina detects an image and a signal is sent to the brain, which interprets what is seen. Some would have us believe that this image is the truth and this is what the artist should strive to achieve in his work, but is what is perceived the truth? If one was daft enough to stand on a railway line and look along its length the rails appear to meet at a point somewhere in the distance. This is often referred to as a vanishing point. However, we know for a fact that railway lines do not meet at a point, otherwise the train would fall off the tracks. So what we see is not the literal truth, but the visual truth. Two forms of truth.

If a person is colour blind the world to that person will look different to a person who can detect the full range of colours. Similarly a fly, which has a multifaceted eye, perceives the world as though looking through frosted glass. If the fly could paint his visual truth it would be quite different from ours, yet he is seeing the same world we see.

It is only in the last 500 years or so, since the invention of perspective in the early Renaissance, that we have become obsessed with the visual truth. This phenomenon happened in the west; in the east things were quite different. Particularly, in Japan, China the emphasis was not so much on the visual truth, but on the literal truth. So a road would be painted parallel, a figure at the top of a mountain depicted the same size as one in the foreground. Why? Simply because people do not shrink because they are further away, neither does a road change shape.

Children from all over the world draw and paint in exactly the same way until around the age of five, when culture begins to exert its influence. A child paints the literal truth, the sky is blue and ‘up there’ the grass is green and ‘down here’. There is nothing in between, hence children’s work will often have a blue strip along the top of the paper and a green one along the bottom. The work of eastern cultures is just as valid as ours, but is based on a radically different concept. What is known to be true rather than what is seen to be true.

Technical Skill – looks like a Photograph

In the 1860’s contact with the east, especially Japan, influenced artists who began to experiment with some of these eastern ideas. This brought these into conflict with the art academics of the time who dismissed their ideas. We can detect this eastern influence in the work of the Impressionists, but perhaps more so in the work of the great post-impressionist artists like Van Gogh, Cézanne and Gauguin. Cézanne, in particular, started to experiment with multiple viewpoints in a picture. If you look carefully at some of his still life paintings you will notice tables have been lifted at different angles to the surrounding objects. This was done deliberately to give the viewer a better view and to get around the limitations of trying to depict a 3D scene on a flat 2D surface. It was Picasso who took these ideas much further. He destroyed the traditional image creating a multi-faceted paintings based on multi-viewpoints.

Once Picasso had made this step it became clear that artists were no longer bound to depict objects in a literal way. The floodgates opened and artists realised shapes and colours could have a life of their own in their own space. More importantly, these shapes and colours could evoke abstract thoughts and meanings and therefore begin to address the areas that figurative art has difficulty in addressing.

Artists, such as Malevich, Mondrian and Kandinsky began to give shape the same relevance as an object and the idea of abstraction was born. These works appealed more to our senses and began to explore other elements of art. They explored the way that we, as human beings, interact with colour, shape, form, texture etc. and the significance these elements can have on our feelings.

In a sense this is what is at the basis of all art. We can distinguish a great portrait, for example by Rembrandt, from that of an amateur painter. The amateur maybe hell bent on capturing a photographic likeness by concentrating on technical skill alone. By contrast, Rembrandt captures the essence of a the sitter by his use of colour, shape, texture etc. Through this he gives us an insight into the soul of the person.

The ability to draw or paint an images so it looks like a photograph is a great technical skill. But it is not what makes an artist great. It is the artist’s vision, the passion, the emotion of his feeling and his/her use of the elements of art that gives us, the viewer, an insight into the meaning of the work. We have to look beyond the technical skill to see what the artist is really trying to convey to us.

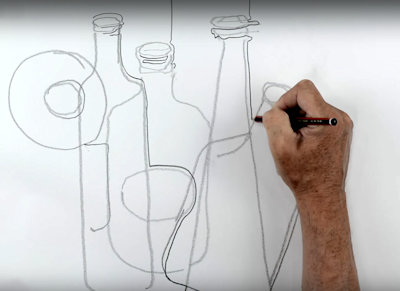

Check out my YouTube Channel

for great How to Draw tutorials designed for children

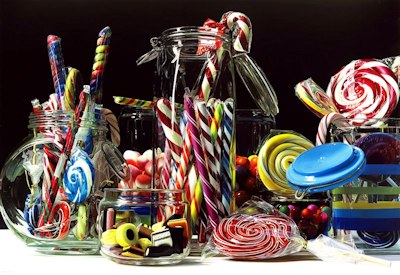

Candy-Rainbow: a painting by Roberto Bernardi

Comments

No comment yet.